European Court annuls Real Driving Emissions limits: the potential consequences

The General Court of the European Union overturned the emissions compliance levels under the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulation in a verdict announced on 13 December. On the surface of it, this may look like a victory for cities wanting to be tougher on emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from passenger cars and vans.

The General Court of the European Union overturned the emissions compliance levels under the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulation in a verdict announced on 13 December. On the surface of it, this may look like a victory for cities wanting to be tougher on emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from passenger cars and vans. In reality, it has the potential to further complicate the Euro 6 regulatory stage and thereby create the unintended consequence of making it even less usable for urban vehicle policy.

While the European Commission did not seek to increase the headline 80 mg/km emissions limit for diesel vehicles, which must still be adhered to in the laboratory test, they granted “Conformity Factors” that in effect did increase the limits for the harder, on-road part of the test. As a result, all diesels vehicles only had to meet 168 mg/km by September 2019, falling to 114 mg/km by January 2021. This was in practice a large increase in the permissible emissions limit.

The Court verdict suggests that vehicles already certified under Real Driving Emissions (that starts with the stage known as “Euro 6d-temp”) will remain compliant, as will vehicles certified for up to 14 further months in the future, depending on whether the Commission appeals and the speed with which replacement legislation is brought forward.

But what is this likely to mean in practice?

Let us assume that there is no appeal and no new legislation, meaning vehicles must meet 80 mg/km on the RDE test. Taking a sample of 30 RDE-certified diesel cars tested by Emissions Analytics on its independent EQUA Index test, we conclude that up to 90% of the vehicles would still be compliant. Although the test does not include cold start in its ratings, overall it remains a good proxy for RDE compliance. Furthermore, the average NOx on a combined cycle of these still-compliant vehicles is just 50 mg/km, well below the certification standard. Of the remaining 10%, they all come from the same OEM, Honda, which would in this scenario need to make changes.

This suggests the impact would be low. However, RDE does not become mandatory for all vehicles sold until September 2019. Therefore, it is likely that this conclusion is flattered due to a self-selecting sample of the best performing cars. If we look at the wider population of pre-RDE Euro 6 diesel cars, we may have a proxy for the challenge to each manufacturer of no Conformity Factors.

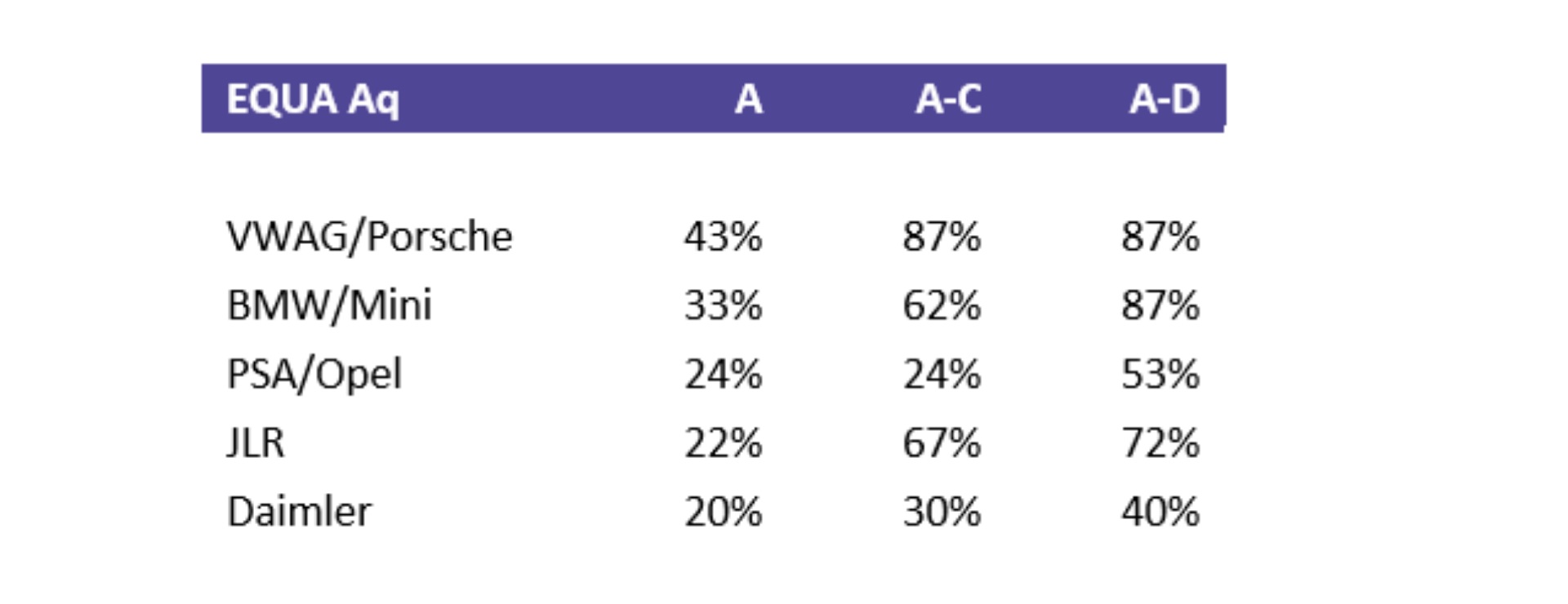

The table below shows the proportion of pre-RDE Euro 6 diesels from a range of manufacturer groups that meet various emissions levels, on our real-world scale. For example, 33% of all BMW/Mini Euro 6 diesel vehicles tested by Emissions Analytics achieve a rating of ‘A’.

The ‘A’ rating is equivalent to 80 mg/km; ‘A’ to ‘C’ is equivalent to 180 mg/km (the Euro 5 level, close to the 2.1 Conformity Factor level); ‘A’ to ‘D’ is equivalent to 250 mg/km (Euro 4).

Approximately, the Conformity Factors allowed ratings of up to ‘C’, but with this annulled, ‘A’ ratings would need to be achieved. The table lists the five manufacturer groups that would be best placed to meet this requirement – assuming their pre-RDE performance is a proxy indicator of how close they are to achieving 80 mg/km across their whole range. VW Group, therefore, is best placed overall; Jaguar Land Rover has made the most rapid advances in the last year.

The final column of the table indicates the proportion that meet ‘A’ to ‘D’. This is relevant to the 270 mg/km maximum limit proposed in an agreement between the German government and cities, to be judged in real-world conditions. The ‘D’ rating is a near equivalent to this level. While the 270 mg/km limit is currently only proposed to apply to Euro 4 and 5 diesels, in time it could be extended to Euro 6 vehicles. If this were to happen, the table shows what proportion of these manufacturers' vehicles may be restricted from the 14 German cities cited. Therefore, VW, BMW and JLR would be the least affected of all. In addition, this is before the benefit of the fixes and retrofits that have been, or may be, actioned, which would further reduce the restrictions. In contrast, there are manufacturers that could face having all their Euro 6 diesels restricted.

Overall, this may give reassurance to some, but there is a wider risk. The annulment of these Conformity Factors further confuses what “Euro 6” means as a label of performance. RDE was meant to be a discontinuity with the past, failed regulation. It had two levels already – two Conformity Factors – but the effect of the Court judgement could lead a change in the gradations or, potentially, more gradations. The Euro 6 label has limited informational content already, but the effect may be to cloud what RDE means, causing further consumer confusion, which would not be to the advantage of the car market.

The Court judgement is witness to the growing power of cities in determining vehicle emissions policy, even if they sometimes demonstrate an unresolved tension between whether air quality improvement or greenhouse gas emissions reduction is the higher priority. What the Court judgement may do is bring into starker relief the difference between the best and worst performing vehicles, which would pave the way for more efficient solutions to the urban air quality challenge.

Real Driving Emissions is a tough regulation, but also a risky one

Aggressive driving on average increases pollutant emissions by 35% in rural driving and by around five times on the motorway, according to testing of the latest passenger cars by Emissions Analytics on its EQUA Index programme.

Aggressive driving on average increases pollutant emissions by 35% in rural driving and by around five times on the motorway, according to testing of the latest passenger cars by Emissions Analytics on its EQUA Index programme. Even higher “hotspots” have also been identified, where emissions at high speed can peak at more than ten times typical levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) – the pollutant gas that was at the centre of the #dieselgate scandal.

The need to identify hotspots is becoming vital with the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulations, which is a much tougher regulation of driving in normal conditions. The consequence of this will be that a greater proportion of total emissions may be concentrated in a small number of more unusual or extreme events. Unless those are well understood, the effect of the new regulations may be blunted.

The in-use surveillance requirements set out in the fourth package of RDE are aimed at monitoring vehicle compliance in all normal driving conditions, not just the cycle on which the vehicle was certified. Broadly, a vehicle should pass any RDE test within its useful life, whenever and whoever conducts the test. This is both a significant challenge for manufacturers, and brings with it risk as it is impossible a priori to guarantee compliance on all possible RDE tests.

To help quantify this risk, Emissions Analytics is launching a new evaluation programme that will quantify the risk of excessive emissions for each vehicle tested. Currently, EQUA Index ratings (www.equaindex.com) are published to allow the performance of different vehicles to be compared on a standard, normal cycle. This new programme leaves that rating unchanged, but puts the vehicle through an extended test designed to measure performance in more extreme and unusual driving conditions. The variance between that, the standard EQUA Index and the regulated level will yield a rating for the risk of exceeding the regulated level.

The main factors considered are:

Higher speeds

Higher and lower rates of acceleration

Cold start emissions

Emissions under regeneration of the diesel particulate filter.

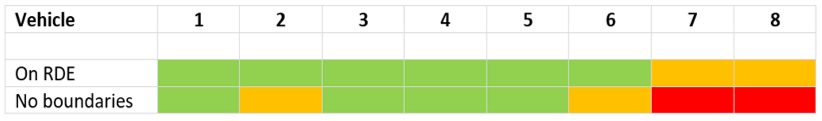

Considering eight diesel cars certified to the new RDE standard (Euro 6d-temp), the effect of driving at speeds up to 160 kph can be shown in the chart below.

In all cases the NOx emissions on the standard cycle – with maximum speeds up to 110 kph – are within the regulated limit of 80 mg/km plus 2.1 times conformity factor, even though certification does not apply this to the motorway section separately. In fact, many of the vehicles are comfortably below this limit. Allowing the maximum speed to rise to 160 kph shows significant proportionate increases on all but one vehicle, with the average percentage increase across all eight vehicles being 552%. All but two of the vehicles remain below the limit despite the increases; however, the worst two vehicles emitted around 650 mg/km.

For reference, under the RDE regulation, the vehicle’s velocity can be driven between 145 and 160 kph for up to 3% of the total motorway driving time. The risk of compliance therefore comes from a vehicle that has a significant emissions uplift at 160 kph and is relatively close to the limit at more moderate speeds.

Under cold start, vehicles 7 and 8 also showed an average increase in emissions of 160% compared to an average of 110% across the other vehicles.

Putting this data together with performance in other parts of the test cycle, it is possible to derive ratings of the risk of excessive emissions on RDE and on RDE-like cycles but with more relaxed boundaries, as shown in the table below.

It is important to note that a red rating does not necessarily imply non-compliance but, rather, it identifies elevated risk of non-compliance using results from the Emissions Analytics’ test, which runs a cycle similar to RDE but that is not strictly compliant.

Considering Euro 6 diesels, whether RDE or prior, the effect of cold start is that NOx emissions are 2.8 times higher on average during the cold start phase compared to the whole warm start cycle. During regeneration of the diesel particulate filter NOx emissions are on average 3.3 times higher than in mixed driving with no regeneration. Therefore, the frequency and geographical location of these events can be critical to the overall real-world vehicle emissions.

These results are important for cities, manufacturers and regulators. For cities, it is vital to know that the latest vehicles do not have emissions hotspots that could undermine their air quality targets. For manufacturers, facing third-party RDE testing to check compliance, it is important to quantify the risk of high emissions being found in unusual driving conditions, where every scenario cannot practically be tested. For regulators, it is important that RDE is seen to function well in order to draw a line under the failed regulation of the past.

Emissions Analytics will continue to test a wide range of the latest vehicles to publish comparable ratings between vehicles, but now with the added quantification of the risk of elevated emissions around the boundaries of normal driving.

Discrepancies between best and worst diesel cars reaches record high

The first diesel vehicle that met the regulated Euro 6 limit for nitrogen oxides (NOx) on our real-world EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) test using a Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) was in May 2013.

The first diesel vehicle that met the regulated Euro 6 limit for nitrogen oxides (NOx) on our real-world EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) test using a Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) was in May 2013. Of the vehicles we tested in that year, the cleanest 10% of diesels emitted 265 mg/km and the dirtiest 10% emitted 1777 mg/km – a ratio of 7 to 1. In 2017, the cleanest 10% achieved an impressive 32 mg/km, but the dirtiest 10% were 1020 mg/km, a ratio of 32 to 1.

On average, progress has certainly been made, with average diesel NOx emissions having fallen from 812 mg/km to 364 mg/km from Euro 5 to Euro 6, or a 55% reduction, driven by the prospect of the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulations together with the aftermath of dieselgate. The very worst vehicles have now disappeared from the new car market. It is also true that in around 10 years’ time, the majority of diesels on the road are likely to be of the cleaner variety, through natural turnover of the fleet.

We have now tested six of the latest RDE-compliant diesel vehicles, also known as 'Euro 6d-temp'. Their average NOx emissions were 48 mg/km, 40% below the regulated limit itself, and 71% below the effective limit once the Conformity Factor of 2.1 is taken into account. (As ever, it should be noted that while the EQUA Index test is broadly similar to an RDE test, it is not strictly compliant.) However, it should be noted that there are many cleaner diesels even before RDE, with 30 prior models achieving real-world emissions of 80 mg/km or less.

While this sounds like good news, the elongated transition to RDE, and growing spread from the best to the worst, are creating a growing policy and consumer choice problem in the meantime. A vehicle in the highest-emitting decile today will likely be a significant contributor to urban NO2 pollution. Yet, the cleanest diesels are getting close to the average NOx emissions from new gasoline vehicles, which is 36 mg/km. Without the contemporary data to show this, policy makers would be forgiven for simply banning all diesels from urban locations.

The lowest NOx emission recorded so far this year is the 2017 model year Mercedes CLS, with selective catalytic reduction after-treatment and type-approved for 6d-temp, which recorded 15 mg of NOx per km.

New Real Driving Emissions regulation increases pressure on annual inspection and maintenance testing system

The European Union Roadworthiness Directive came into force on 20 May 2018 and will play a role in enforcing type approval emissions limits, subtly but powerfully changing its role and previous focus on safety, to the benefit of air quality.

The European Union Roadworthiness Directive came into force on 20 May 2018 and will play a role in enforcing type approval emissions limits, subtly but powerfully changing its role and previous focus on safety, to the benefit of air quality.

In the new inspection and maintenance test, known for example as the MOT test in the UK, a ‘major’ defect and automatic fail arises from any visible smoke being emitted by any car equipped with a diesel particulate filter (DPF), meaning in practice the majority of vehicles since late 2009 (Euro 5 onwards).

The definition of ‘visible smoke’ has only tightened up for vehicles registered after 1 January 2014, meaning late Euro 5 and all Euro 6. Permitted smoke for these cars has more than halved from 1.5m-1 to 0.7m-1. This measurement is familiar to any MOT tester and denotes opacity, where 0.0 m-1 is totally clear and 10.00 m-1 is totally black. In practice, less than 0.7m-1 is judged to be invisible and more than 0.7m-1 will be visible.

For vehicles from 1 July 2008 to 31 December 2013, the standard is 1.5m-1, while the smoke standard for older cars remains unchanged, at 2.5m-1 (non-turbo) 3.0m-1 (turbo).

Air quality campaigners have been quick to note the perversity of a tougher test that only applies to newer cars. However, it has long been politically unfeasible to apply new standards to old cars, which would see the wholesale removal of vehicles that met their type approval at the time of their manufacture.

The revised smoke test for vehicles since 2014 is likely to catch out cars where the DPF is absent or defective. Particulate emissions rise by orders of magnitude when the DPF is missing or blocked. In the UK, 1800 cars have been caught without a DPF since 2014, but the true figure is believed to be much higher because it is notoriously difficult for testers to identify DPF removal in the small amount of time taken to perform the MOT.

In an exercise Emissions Analytics conducted in 2017 with BBC 5 live Investigates, a car with its DPF removed still passed its MOT at three (out of three) different garages. Mechanics failed to spot the filter had been taken out on each occasion, and the car was not failed for opacity.

To quantify the difference between having a DPF and not having a DPF, Emissions Analytics technicians tested a 9.0 litre commercial diesel engine before and after the installation of a DPF retrofit. The particle number (PN) and particle mass (PM) afterwards were close to zero, so the reduction was over 99%. Therefore, tampering would increase the emissions by orders of magnitude.

As this problem of DPF removal detection has not been eliminated, it is believed that the tougher smoke test will most likely identify missing filters, although we think a greater degree of tester training and adherence to test processes is also required.

A weakness of the new test is that is does virtually nothing to enforce emissions limits for nitrogen dioxide (NOx). Emissions control equipment is only subject to a visual check for its presence, including the oxygen sensor, NOx sensor and exhaust gas recirculation valve.

Should any of these items be ‘missing, obviously modified or obviously defective’, the car fails the test. However, the new (UK) MOT Manual skimps over this area by suggesting in section 8.2.2.1 (Exhaust emission control equipment for diesel engines), telling testers, “You only need to check components that are visible and identifiable, such as diesel oxidation catalysts, diesel particulate filters, exhaust gas recirculation valves and selective catalytic reduction valves.” We suspect that in numerous cases this requirement will be neglected owing to the continued difficulty of determining the presence of some of these items, or because of commercial pressures to complete tests quickly.

Almost all Euro 5 diesel cars had no NOx after-treatment, just exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), while their Euro 6 successors typically received the addition of either a Lean NOx Trap (LNT) or a Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system. Therefore, as a rough equivalence, a Euro 6 car with failed after-treatment may emit at a level more akin to an equivalent Euro 5 vehicle.

Emissions Analytics has tested numerous Euro 5 and 6 cars on its on-road EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) route. For example, a Euro 5 VW Golf 1.6 litre diesel emitted 0.557 g/km of NOx, while its LNT-equipped Euro 6 successor emitted 0.161 g/km, a reduction of 71%.

Then take the larger Mercedes C-Class 2.1 litre diesel. In Euro 5 guise it emitted 1.226 g/km of NOx; and with SCR fitted to the Euro 6 version the same engine emitted 0.396 g/km, a reduction of 68%.

From these results it is clear that to disable these treatments (with an “emulator” or similar) or where they have malfunctioned, NOx could increase by a factor of over 3.

However, the dilemma in setting an in-service NOx standard is that the performance of vehicles when brand new varies from around 20 mg/km to over 1500 mg/km – the issue uncovered as a result of the dieselgate scandal. A vehicle normally producing 20 mg/km that is malfunctioning might produce 800 mg/km, whereas a different model may produce 800 mg/km when in a fully functioning condition. Therefore, a real-world reference number is required to judge the in-service performance. The EQUA Index rating, which is a standardised test on the vehicle when new, could act as this reference value to increase the accuracy of identifying malfunctioning vehicles.

One unmistakable outcome is that what was once mainly a test for roadworthiness has now become a more complex enforcement of type approval emissions, at the very moment when those limits are tightening up within WLTP/RDE.

The inspection and maintenance system has in this sense risen in importance as a tool for policing emissions, because non-compliant vehicles will display vastly increased emissions, by orders of magnitude. However, the failure to test properly for NOx misses one of the major problems that Europe faces, in the wake of its dieselisation, while the ultrafine particles produced by downsized, direct injection petrol engines are also missed. It feels as though the new test is distinctly lacking in these crucial areas, leaving much more work to be done.

Rethinking Scrappage For Addressing Vehicle Emissions

Scrappage schemes are controversial. In a 2011 academic paper* reviewing 26 studies assessing the outcomes of 18 scrappage schemes implemented around the world in 2008-11, the authors concluded that the emission effects of the schemes were ‘modest and occur within the short term.’ They also concluded that the cost-effectiveness of such schemes ‘is often quite poor.’

Scrappage schemes are controversial. In a 2011 academic paper* reviewing 26 studies assessing the outcomes of 18 scrappage schemes implemented around the world in 2008-11, the authors concluded that the emission effects of the schemes were ‘modest and occur within the short term.’ They also concluded that the cost-effectiveness of such schemes ‘is often quite poor.’

The reality of the 2008-9 scrappage schemes, however, was that governments in Europe, the US and Japan were tackling a liquidity gap by stimulating consumption and bolstering an ailing car industry. The mooted environmental benefits of accelerated fleet renewal were talked up by politicians but were not the main objective. This helps to explain why the efficiency of the schemes in mitigating Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions - CO2 dominating discussion at the time - was found to be poor value for the taxpayer and of marginal consequence to overall path reductions towards a low carbon economy.

Since 2008-9, the policy climate has changed significantly, with air quality emerging as a major concern. Several national governments have been sued by environmental groups for illegal levels of NOx in cities, and what was once a transport policy issue has become a matter of public health. With diesel bans looming in city centres, plus the advent of clean air zones, it’s no stunt to reimagine scrappage according to an emission-reduction imperative.

Data availability upon which to base an intelligent scrappage scheme has also improved. Since 2011 Emissions Analytics has compiled the world’s largest database (the EQUA Index) of standardised real-world emissions tests, of over 2000 cars. The EQUA Index test measures not just CO2 emissions but nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon monoxide (CO), as well as fuel efficiency.

Reimagining scrappage in light of air quality first requires accepting that the now discredited New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) test regime has produced counterintuitive outcomes, to the point where some of the newest cars are by no means the cleanest. This means that a poorly designed scrappage scheme could produce a worse outcome, measured in air quality, than doing nothing at all.

The EQUA Index results show that:

Dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are 6-7 times worse than cleanest Euro 5

Dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are up to 3 times worse than cleanest Euro 3/4

Some 20-year-old cars are cleaner than some brand new cars

How one weights GHG emissions against NOx emissions is a matter of policy debate and public acceptance, but a plausible objective would be Pareto optimality, or the idea that addressing air quality should not be at the expense of GHG such as CO2. While research points towards life cycle or ‘well to wheel’ analysis of CO2 emissions, this is difficult to measure and for the sake of a near-term scrappage scheme probably lies in the future.

Beyond the well-observed conflict between efficiency, where diesel scores well compared to gasoline, and the point-of-use emissions, where gasoline is consistently cleaner with respect to certain emissions such as nitrogen dioxide, the point to make is that it is possible to target and scrap dirty cars without increasing CO2.

The EQUA Index test recently revealed that 11 Euro 6 diesel cars from four manufacturers merited an A+ rating, equivalent to 0.06 g/km NOx in the EQUA Index test, which compares with a limit 180% higher (0.168 g/km NOx) for the new RDE requirement that will prevail until January 2021. Such cars can be said to be genuinely clean by today’s standards, but were greatly outnumbered by highly polluting diesel models, 38 of which scored F, G or H, meaning that they exceeded the Euro 6 limit in respect of NOx by 6-15 times. By comparison, 105 gasoline and hybrid Euro 6 cars achieved the A+ rating, and only one gasoline model fell into the D category, the rest being C or higher.

In the graph above, the arrow labelled ‘Bad Trade’ travels from a Euro 4, 1.9-litre diesel Skoda Octavia, model year 2009, that scored E in the EQUA Index test, towards a Euro 6, 1.6 litre diesel Nissan Qashqai, model year 2016, that scored H in the EQUA Index test. The Skoda is cleaner than the Nissan in real-world testing, yet a scrappage scheme designed around vehicle age alone could result in the cleaner Skoda being scrapped for purchase of an equivalent, dirtier Nissan Qashqai. This would result in tailpipe emissions higher by a factor of more than five and therefore worse air quality. It would be a waste of tax payer money.

Conversely the ‘Good Trade’ arrow highlights that dirty older (and conceivably newer) vehicles could be scrapped for genuinely cleaner new vehicles. Currently, 87% of Euro 6 diesel cars are over the Euro 6 limit, as are all Euro 5 cars. If all these cars were replaced by Euro 6 cars actually performing to the Euro 6 diesel standard in real-world conditions, the net tailpipe emissions improvement measured in NOx would be around 88% from the Euro 5/6 fleet. If real-world performance were only brought down to the Euro 5 diesel standard, the reduction in emissions would be 74%. Even if performance were reduced to just Euro 3 levels, there would still be a 38% reduction.

Put another way, as most Euro 5 and 6 diesels emit over the limit, a large number of vehicles need to be “fixed” to address the air quality problem. This inherently makes any scrappage scheme highly costly. Therefore, a more stratified approach may be optimal, as shown in the chart above. Emerging passenger car retrofit technology may deliver a 25% or more reduction in NOx; those vehicles with moderately high emissions could be tackled in that way. A scrappage scheme could then be targeted on the dirtiest diesels (perhaps worse than the Euro 3 level in real-world).

A further potential ‘Bad Trade’ may be switching from a diesel car to a non-hybridised gasoline car. The same vehicles viewed through the lens of CO2 emissions show that on average, gasoline vehicles are, like-for-like, a ratings class worse than diesels for absolute CO2 emissions. They also exhibit a greater disparity between NEDC measurements and actual emissions. For example, the 2017 Audi Q2 diesel, achieves A+ for air quality and C2 for CO2. The same power output gasoline equivalent model from the same year also achieves A+ for air quality, but a lower D4 for CO2. C means 150-175g/km CO2; D means 175-200 g/km, but the numbers 2 and 4 respectively show that the gasoline engine model is at greater variance from the officially claimed figures. This example highlights an element of the trade-off involved if tackling air quality results in a more gasoline-dominant fleet.

In summary, the right scrappage and retrofit schemes could incentivise consumers towards vehicles that are genuinely clean and genuinely efficient, taking into account not just NOx emissions, but also CO2 and particulates. This would contrast with the UK’s 2009 scheme that merely required customers to scrap their old car for any new vehicle. A stratified and discriminating scheme would require a more focussed replacement, resulting in better results both for air quality and climate change.

* Bert Van Wee, Gerard De Jong & Hans Nijland (2011) ‘Accelerating Car Scrappage: A Review of Research into the Environmental Impacts’, Transport Reviews, 31:5, 549-569, DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2011.564331

Cutting pollution and improving public health

Pollution is a major contributor to chronic human sickness, not just environmental damage, according to the 2017 annual report of England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, released on 2 March 2018: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know. The report made 22 policy recommendations, many of which related to monitoring and ameliorating pollutant emissions.

Pollution is a major contributor to chronic human sickness, not just environmental damage, according to the 2017 annual report of England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, released on 2 March 2018: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know. The report made 22 policy recommendations, many of which related to monitoring and ameliorating pollutant emissions.

Emissions Analytics is pleased to have had its EQUA Index real-world emissions rating system (www.equaindex.com) cited in the report. With the failure of the previous EU vehicles emissions regulatory regime, having led to around 40 million high-NOx-emitting diesels on European roads, the need to base policy on real-world emissions has grown, as illustrated in the chart below. Each point represents a vehicle we have tested, and the horizontal line shows the regulated limits.

It is clear that at each Euro stage the cleanest vehicles have been getting cleaner, while the dirtiest vehicles have not. Therefore, any system of discriminating between vehicles based only on Euro stage will be highly inefficient as it will involve permitting some vehicles with high real-world emissions. The particularly problematic Euro stages are 5 and 6, within which there are significant spreads from the best to the worst. For example, the dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are six to seven times higher emitting than the cleanest Euro 5. More striking still, the dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are around three times worse than the cleanest Euro 3/4 vehicles, last of which were type-approved in 2009.

In summary, using the EQUA Indices would allow governments and cities to target only those vehicles which are high emitting in practice, minimising the private and public cost. Any system based only on official Euro standards would be costlier and less efficient. Estimates of the benefit suggest that 54% of Euro 6 diesels would have to be restricted from urban areas to achieve an 87% reduction in nitrogen oxide emissions.

Many of the Chief Medical Officer’s recommendations revolve around the need for evidence-based action. This has been dramatically lacking in emissions policy, due to the difficult choices it would present.

One recommendation specifically calls on local government and public health professionals to implement concrete solutions. The Mayor of London’s publishing of the EQUA Aq ratings for NOx on its official website (www.london.gov.uk/cleaner-vehicle-checker/) is an example of proven action that could be applied in any city across Europe. Another recommendation talks about providing toolkits to assist local authorities. With the challenges of Clean Air Zones, the priority is to link up the existing empirical evidence with policy action on the ground.

An example of this is when regulating against particulate number emissions: current certification of particle number (PN) emissions is down to 23 nanometres in size. However, ambient pollution laws still focus on PM2.5, or 2500 nanometres in size. The concern about ultrafine particles has been growing, as the penetration of direct injection gasoline engines has increased.

Latest test data from Emissions Analytics also suggests than certain diesels are now lower in CO2, carbon monoxide (CO) and PN emissions that many gasoline cars, and equivalent levels of NOx. This should be carefully borne in mind as policy increasingly slants away from all diesels.

The Chief Medical Officer’s report also recommends a standardised approach to pollution surveillance and road charging to give vehicle drivers a simple and consistent system. While the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulation is robust, it is not simple and consistent, which will limit its effect in rebuilding consumer trust. In particular, previously launched cars will not be systematically retested on RDE and therefore there will be no comparability with new cars.

Finally, the current lack of trust in car manufacturers is not to the benefit of them, consumers, the market or society. A further recommendation calls for transparency on the part of industry as to the polluting effect of their activities. Emissions Analytics believes this is a necessary first step to rebuilding that trust.

Emissions Analytics hopes the simple, independent and free-access nature of the EQUA Index is a good place to start to reassert evidence-based policy and the health of the automotive industry.

Archive

- AIR Alliance 3

- Air Quality 38

- Audio 3

- Climate Change 14

- EQUA Index 21

- Electrified Vehicles 28

- Euro 7 3

- Fuel Consumption/Economy 20

- Fuels 4

- Infographic 18

- Media 4

- NRMM/Off-road 3

- Newsletter 103

- Podcast 7

- Presentation/Webinar 18

- Press Release 19

- Regulation 16

- Reports 4

- Tailpipe Emissions 49

- Tyre Consortium 2

- Tyre Emissions 26

- Vehicle Interior 6