Burning Issue: Tyres And Air Quality

Are tyres replacing tailpipe as the policy priority?

Are tyres replacing tailpipe as the policy priority?

Tyres are rapidly emerging as a new source of environmental concern and this will affect the car industry.

In a recently aired BBC radio documentary, it was claimed that the world will discard 3 billion tyres in 2019, enough to fill a large football stadium 130 times1. Beyond this broad issue of resource use and material waste, tyres also sit uniquely at the intersection of air quality and microplastics.

This newsletter sketches the problem in its current form and considers certain automotive developments in its light.

As a car drives by, you cannot see its tyres wearing and therefore ‘tyre wear’ in this sense remains imperceptible except in deliberately extreme use such as branches of motor sport such as drag racing and drifting.

Yet over a lifetime of between 20-50,000kms, a tyre will shed approximately 10-30% of its tread rubber into the environment, at least 1-2kgs2. The wear factor (defined as the total amount of material lost per kilometre) varies enormously depending on tyre characteristics such as size – radius/width/depth – tread depth, construction, pressure and temperature. In one recent Emissions Analytics’ test, conducted under real-world rather than lab conditions, the four tyres on a standard hatchback lost 1.8kg over just 200 miles of fast road speeds, far in excess of what had been anticipated by the testers.

A tyre abraids owing to the friction between its contact patch and the road surface. It ‘emits’ particles across a broad size spectrum, from coarse to fine to ultrafine to nanoscale. It may also emit other forms of aromatics such as benzopyrene and benzofluorene, the result of the incomplete combustion of organic matter resulting in evaporation of the volatile content of the tyres, which the EU has regulated to a degree3.

Coarse particles typically fall rapidly to the ground. At the fine level and smaller, they are airborne for a certain duration, either being blown away from the carriageway before settling on the ground, or falling to the carriageway where re-suspension may take place as other vehicles pass.

Particle dispersion and deposition eventually occurs, but that is not the end of the story. The particles typically pass into the watershed through street drainage and are estimated to be a primary source of as much as 28% of microplastics found in the marine environment4.

The recent re-characterisation of tyre wear emissions as ‘microplastic pollution’ corrects the broadly misleading public idea, out of date a hundred years and counting, that tyres are composed principally of natural rubber. Instead, tyres are a close derivative of crude oil and their wholesale pricing typically tracks it.

A typical car tyre comprises 45% oil-derived synthetic rubber (polymer), 40% oil-derived carbon-black (filler, 40%), and 15% various additives to aid production processes, some of which typically contain heavy metals and some of which are also oil-derived.

Some tyres contain natural rubber, but to all intents and purposes we live in the age of the plastic tyre.

For not unrelated reasons, we also live in the age of the disposable tyre. From being an expensive product derived in large part from natural rubber, tyres have fallen in cost as globalisation has catapulted numerous new entrant tyre-makers into what is today a $240bn a year industry.

If we now turn to the automotive world, tyres are more important than ever to vehicle attractiveness and performance, but for many different reasons:

An emphasis on vehicle and tyre performance is often at the price of tyre longevity, particularly where higher diameter wheel rim sizes are combined with wide tyres, whether to convey power or sportiness

Tyres have become more disposable as their price has fallen in real terms, replacing an older tradition of re-treading carcasses for extended life

New entrant tyre-makers in Asia, South Asia and Eastern Europe have led to the advent of the ‘budget tyre’

Electric vehicles offer instant torque and higher kerb weights, implying higher tyre wear rates, even while regenerative braking is expected to reduce brake wear emissions

Electrification leads to a completely new appraisal of the tyre in respect of durability and noise

In-cabin tyre noise becomes a high-concern consumer issue as drivetrain noise is reduced or eliminated.

From a regulatory viewpoint, tyres in Europe are labelled according to three criteria, (the so-called ‘performance triangle’): rolling resistance, wet grip and noise – but that may change as tyre environmental impact rises up the political agenda.

From our perspective, Emissions Analytics has been conducting in-depth real-world tests on tyres. Two immediate insights can be shared:

Budget tyres wear rapidly and have high emissions

New instrumentation capable of measuring emissions down to the nanoscale shows that at the ultrafine level and smaller, the particle mass becomes far less instructive than the particle number, which is much more significant, and yet current regulations only measure mass

The size distribution has potential implications for the epidemiology (health) concern around very fine particulate matter and how it may affect human health.

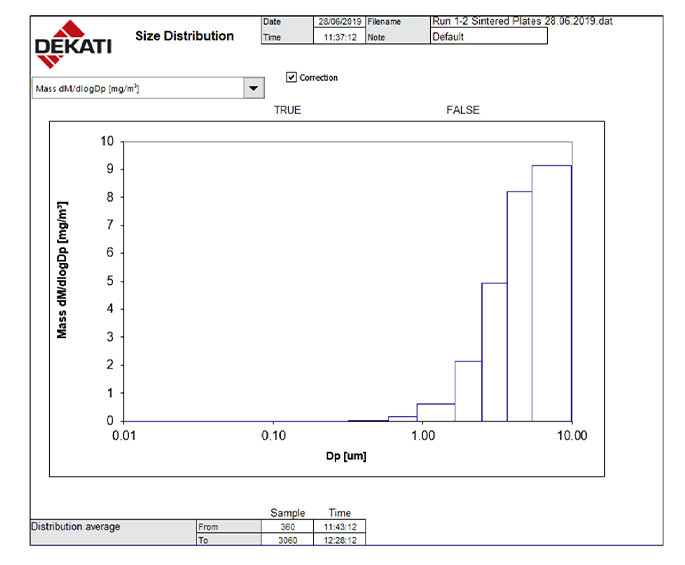

In one recent test, Emissions Analytics used a Dekati ELPI+ (Dekati® ELPI®+ Unit standard with 14 size fractions from 6nm up to 10um for PN/PM concentration at 1Hz/10Hz sampling rate) to measure both particle mass and number. The first chart below shows the resulting mass distribution.

We regard this as a valuable piece of data even though it only corroborates what is broadly known, that a comparatively small number of coarser particles (up to and including the 10 micrometre size shown in the far right column, familiar as PM10) account for most of the recorded mass.

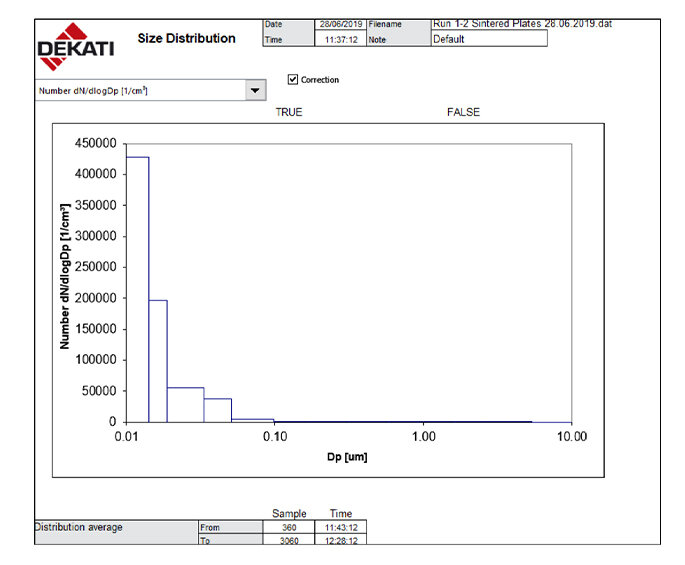

Then consider however the contrast when particle number is accounted for rather than mass: you get a mirror of the first graph, with a tiny amount of mass expressed as a very high number of nanoscale particles right down to the 10-nanometre level expressed in the first column (0.01 micro-metre).

This is a potentially valuable insight because until now this high particle number count has typically either not been measurable or not been measured, owing to a regulatory preoccupation with mass and a lack of suitably sensitive real-time measurement instrumentation.

The ability to count particles down to 10 nanometres relies on the quality of the impactor chosen for this test, which is considered to be the best currently available on a commercial basis.

Regarding public health, there is a tentative emerging consensus among epidemiologists and other medical researchers that ultra-fine particles are potentially more injurious to human health than coarse particles, owing to their ability to translocate to the bloodstream through the lungs5.

Particles will need to continue to be measured both for their mass and their number. In respect of mass they are emitted in a large size range by tyres. In respect of number they emitted in high volumes.

We highlight the UK government’s recent report Non-Exhaust Emissions from Road Traffic, authored by the UK Government’s Air Quality Expert Group (AQEG). It recommends “as an immediate priority that non-exhaust emissions (NEEs) are recognised as a source of ambient concentrations of airborne PM, even for vehicles with zero exhaust emissions of particles.”

Quite apart from the broader point here that so-called ‘zero emission vehicles’ are in fact significant sources of non-exhaust emissions, the quantity of such emissions is set to rise.

The same UK government report notes that non-exhaust emissions are believed to constitute today the majority source of primary particulate matter from road transport, 60% of PM2.5 and 73% of PM10. While regenerative braking is expected to reduce brake wear emissions, the increased weight and torque characteristics of alternative drivetrains such as EVs will likely be associated with increased tyre wear.

In the same report it is suggested that a 10kg increase in vehicle mass accounts for a 0.8-1.8% increase in nanoparticle emissions from tyres. This is particularly relevant as a whole generation of new EVs is hitting the roads with considerably larger and heavier battery packs than in the past.

For small to medium cars, where modest range is acceptable for city use or where the glider (bare chassis) has been deliberately lightweighted to offset batteries (as per the BMW i3), the weight gain may be marginal. Indeed, a switch to narrow tyres may neutralise or even reduce tyre wear.

But a Tesla Model S or Model X, Mercedes EQC, Audi e-tron or Jaguar i-Pace, EVs with larger ranges and battery packs in the range of 60-100 kWh, weigh 2.3-2.6 tonnes. The 600kg battery pack in the Mercedes EQC would on the AQEG/DEFRA model potentially increase nanoparticle emissions from tyres by 48-108%, compared to a conventional vehicle weighing 600kg less.

The same argument can be extended to internal combustion engine vehicles. A heavier vehicle increases tyre wear, whereas lightweighting mitigates it. This has implications for the broader market trend towards SUVs, where often particularly large rim tyre sizes are adopted.

On this basis we think tyres are set to be scrutinised and regulated more, and perhaps also reinvented for electric cars to perform well in durability and noise. There will be opportunities and threats that arise from these changes.

We anticipate the need to place a value on low emission tyres, so that they are desired and consumers are willing to pay for them, in other words using a tax policy that internalises the externality to the benefit both of society and the environment.

1 Costing the Earth: Tread Lightly. BBC Radio 4, March 13th, 2019.

2 Grigoratos & Martini, 2014.

3 Since 2010 the EU has required the discontinuation of the use of extender oils which contain more than 1 mg kg−1 Benzo(a)pyrene, or more than 10 mg kg−1 of the sum of all listed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the manufacture procedure due to increased health concerns related to PAHs (European Commission, 2005).

4 Microplastics are considered to be all plastic particles in the range of 0.1–5,000 µm. A secondary source is when a larger plastic object breaks down once already in a marine environment. The figure of 28.3% was originally cited in Julien Boucher, Damien Friot, Primary Microplastics in the Oceans: a Global Evaluation of Sources, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, 2017, p21.

5 Newby, David: ‘Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease - A Mills and Boon Classic’ (2019).

Plug-In Hybrids Without Behavioural Compliance Risk Failure

Tensions between official EU emissions policy and member states.

Tensions between official EU emissions policy and member states.

When the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) commenced in September 2017, it replaced the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) with a more realistic, ‘real-world’ approach to emissions testing. Following this switch, several models of plug-in hybrid car (PHEV) were withdrawn from sale in Europe as their emissions ‘rose’ sharply under the new test, disallowing them from various subsidies and benefits. Yet interestingly a wide range of new PHEVs are now being launched, two years later.

The new crop of PHEVs are likely to have been optimised to the WLTP emissions test, and come with larger batteries in the range of 10-30kWh instead of previously 3-6kWh. This ensures that they achieve super-credit status, or sub-50g CO2/km emissions ratings, which initially allows them to be counted twice in the fleet average CO2 calculation. This is vital for manufacturers who have to meet impending fleet average emissions targets of 95g/km from 2020 or face large fines in Europe.

This strong incentive from the EU level directly clashes with some member state policies: national governments that have cancelled generous subsidies for all PHEVs. This group of policy makers are suspicious of PHEVs.

The Dutch government, followed by the British, in late 2018, withdrew previously generous PHEV subsidies. They cited evidence suggesting that many owners, attracted by a subsidy, rarely plugged in their PHEVs.

So what is going on and who is right? If a PHEV is not plugged in, it typically drives around on a smaller than optimal internal combustion engine and achieves poor real-world results.

Of all PHEVs tested by Emissions Analytics, which includes petrol and diesel versions, the average performance in this condition is 37.2 mpg (7.6 l/100km) and CO2 emissions of 193.3g/km, which is 62.5% worse than the official NEDC results.

By no stretch of the imagination are these compelling figures if, as EU policy makers would claim, the purpose is to reduce real greenhouse gases as quickly as possible.

That is not to say that PHEVs have no claim to virtue. Their primary strength is offering electrification without range anxiety, since an internal combustion engine remains present, whether as a part of the drivetrain or as a ‘range-extending’ battery generator.

However, one of the challenges for PHEVs is that by the nature of the technology, their performance cannot be properly encapsulated and articulated by the standard, cycle-based rating. Rather, the real-world performance of PHEVs rests to an unusually large degree on user behaviour and journey length, rather than instantaneous combustion performance.

Research studies have shown that some duty cycles – for example commuting to and from work every day but charging overnight and avoiding long distances – can result in virtually no use of the ICE. The consumer has in this case had an EV ‘on the cheap’, without the weight and cost of a large battery pack. This is a PHEV at its best.1

At the other end of the spectrum, a PHEV might be deployed on long journeys and never plugged in. This results in a significant disbenefit, the vehicle typically offering worse fuel consumption and emissions than a conventional ICE-only drivetrain. This is a PHEV at its worst.

While we can recognise that many current or potential PHEV owners understand that the electric driving share of a PHEV, expressed as its utility factor (UF), is the key to its fuel economy rating and emissions, nonetheless the Dutch data, based on fuel card usage, included a significant business user fleet where there was evidently no fiscal incentive to save fuel. These owners were hardly plugging in.2

In the study referenced in footnote 1, based on 1831 Chevrolet Volts in the US, the authors found generally excellent utility factors, the average being 78%. In the Dutch data, which included smaller-battery PHEVs and owners who typically didn’t bother to plug in, the average utility factor was 24%.

If we take this spread, 24-78%, as the real range of utility factor, and return to the Emissions Analytics average PHEV performance of 193g/km CO2, it can be re-expressed as spanning 151g/km CO2 (24% UF), to 46g/km CO2 (78% UF).

The effect of the WLTP has been to force model overhauls, leading to larger internal combustion engines, and larger batteries to achieve longer electric range.

This is precisely what happened with the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, at different times and places the leading PHEV in Europe. To achieve a sub-50g/km result under WLTP the manufacturer fitted a 2.4 litre petrol engine, replacing a 2.0 litre unit, and increased battery size from 12kWh to 13.8kWh. EV range fell from 33 miles under the NEDC to 28 miles under the WLTP, but crucially it allowed the SUV to retain a sub-50g rating (46g/km) as a category 2 Ultra Low Emission Vehicle.

The warning to policy makers is that current and future PHEVs offer most of the same strengths and weaknesses of previous models, and that car makers are optimising their products to achieve the sub-50g result under WLTP but without guaranteeing any actual reduction in emissions.

In a very recent instance one OEM, Peugeot, boasted of an SUV featuring 4WD and 300hp yet 29g/km CO2, premised on an electric range of 36 miles and a 13.2kWh battery. The 3008 SUV GT Hybrid4 qualifies in the UK for the lowest Benefit in Kind (BIK) tax rating of 10%, re-attracting a subsidy.

In another 2019 product launch, the Volvo XC40 T5 Twin Engine claims 262hp and a preliminary WLTP rating of 38g/km. In this instance some but not all variants of this model offer a ‘hybrid’ setting that tries to optimise overall efficiency, except that whether it is deployed or not sits with the owner. Such an innovation is likely to confuse regulators and consumers alike, even if it may also work well in practice.

Our position is that on reasonable assumptions PHEVs will deliver less and less certain reductions in CO2 than non-plug-in hybrids. In other words, that they are ineffective without behavioural compliance, and that such compliance is politically infeasible in most democracies where it would be considered an intrusion on privacy.

The case for future PHEVs may lie principally in the light to medium commercial fleet, where the advent of zero-emission city centres may force dual-drivetrain approaches, the pure electric drive share being saved for last mile delivery and the ICE (diesel as well as petrol) permitting long highway distances, refrigeration units and so forth.

Geo-fencing is also strongly foreshadowed in current fleet management, from public bus fleets to Uber’s app, and suggests a straightforward way to ‘enforce’ the correct use of a PHEV, thus compelling fleet operators to plug them in.

This would go a long way to addressing the ongoing weakness of the PHEV, its drivetrain sleight-of-hand that courts generous tax-payer subsidy but delivers poor real-world performance.

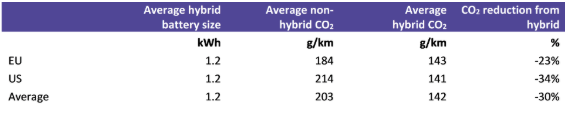

In the realm of private passenger cars, however, we have shown in a previous newsletter how by comparison non-plug-in, full hybrids offer much faster and more certain emissions reductions of up to 30%. Given the importance of reducing CO2 emissions agressively and quickly, the lower risk option may be preferable.

1 Patrick Plotz, Simon Arpad Funke, Patrick Jochem. ‘The impact of daily and annual driving on fuel economy and CO2 emissions of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles’ in Transportation Research Part A, 118 (2018) 331-340.

2 Ligterink, N.E., Eijk, A.R.A, 2014. ‘Update Analysis of real-world fuel consumption of business passenger cars based on Travelcard Nederland fuelpass data’, TNO Report TNO 2014 R11063.

The Promise Of Life Cycle Assessment And Its Limits

Approaches to comparative rating of vehicles.

Approaches to comparative rating of vehicles.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is the principal way to achieve clarity over the environmental credentials of varying drivetrains, and may become the basis of primary legislation in Europe and beyond over the next decade.

The purpose of this newsletter is to consider how LCA can work in practice, bringing clarity to the automotive sector both as an efficient market, the producer of environmentally sensitive products and in respect of consumer choice, i.e. how vehicles might be rated and ranked for their ‘greenness’.

LCA has existed as a concept since the 1970s and is by now a well-established field of academic inquiry. Contrary to common perception in 2019, LCA is not necessarily about CO2 emissions and the climate ‘friendliness’ of one car over another, say diesel versus electric. LCA can equally apply to other impact categories such as social justice or supply chain efficiency, and indeed ‘non-climate’ environmental impact categories such as water use. It is a method for considering the total lifespan of a product, but the chosen theme and system boundaries can be many, and they can be divergent. It can be applied to any product and not just cars. Owing to their material and commercial complexity, cars are among the most challenging products to apply LCA to.

A useful historical note is to remember that a precursor of LCA was Technology Assessment (TA) in the US in the 1960s. The aim of this nascent philosophy was to brief Congress on the likely impact on society and economy of new technologies, to inform intelligent policy decisions.

LCA offers a not dissimilar service today. Conventionally, it relies on a modelling of a vehicle’s impact in four areas: fuel (from source to distribution); vehicle production, vehicle use and end-of-life.

Until recently the greatest emphasis was on the fuel because the use-phase of an internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV) is the dominant source of emissions. With electrification, the emphasis has swung to vehicle production (batteries) and end-of-life (batteries), both about which there remains a lack of usable data. There is no utility scale automotive battery recycling, but it takes place on a small scale. Meanwhile, the estimate of embedded emissions from manufacture as a proportion of total emissions are 15-20% for a gasoline car, but 20-60% for a battery electric car. Recent studies have emphasised the larger figure in that wide range, citing not just the batteries but supporting, high emission components such as aluminium. Meanwhile the fuel question is displaced to the energy grid and looms large in any credible assessment of the environmental claims of EVs.

LCA also casts doubt on the industry’s claim that diesel is better than gasoline in climate terms. In fact a diesel car’s embedded emissions are higher than a gasoline car’s (the range of estimates is 20-30% versus 15-20%, respectively) thanks to the heavier engine block and typically greater emissions controls. Like an electric car it then has to ‘break even’ over its lifetime by offering lower in-use CO2 emissions.

It is worth noting that the academic field of LCA has already moved somewhat beyond these basic LCA applications even though they remain in their infancy and are not typically understood or applied by policy makers, consumers or even parts of the car industry. Current LCA trends are to move beyond product life cycles to consider user patterns and behavioural dimensions.

Rebound effects suffice here as a cautionary note. If a consumer saves fuel costs by buying an electric car, but spends the proceeds on a long-haul flight to the Caribbean, that’s a negative environmental rebound effect. Such whole system thinking demonstrates that beyond the application of LCA to cars there remain wider considerations, including the very desirability of private car ownership given projected global urbanisation rates, resource scarcity and the political imperative towards liveable cities.

Despite all such concerns, the advent of variously electrified drivetrains makes an LCA approach essential, in our view, for the achievement of basic consumer clarity around product claims as well as policy maker insight.

One central objective, echoing previous Emissions Analytics newsletters, is achieving the greatest reduction of CO2 emissions in the shortest possible time, in the real world and not just on paper, so as to achieve the promise of the Paris climate accord and the stated goals of the IPCC in containing climate change.

Unfortunately, almost all existing vehicle regulation in OECD countries is out of sync with this climate objective, having arisen in an era in which the internal combustion engine was overwhelmingly dominant. Existing regulation concerns fuel economy and tailpipe emissions. Because EVs have tank-to-wheel emissions of zero, they have caught the policy-makers’ ear for being ‘zero emission’. Partly as a result, numerous countries have now declared their intention to halt the sale of ICE drivetrain vehicles in coming decades.

Our view of this development is one of caution, partly because of the insight afforded by the application of LCA.

In short, countries such as the UK, India, France and China are moving towards outright bans on internal combustion engines before regulators have established even rudimentary frameworks for lifecycle carbon emissions of vehicles.

It is not widely understood in the West that China’s push into rapid electrification is primarily to address poor air quality rather than combat climate change. In LCA terms its electric cars are at best roughly on par with their ICEV equivalents, with small gains predicted by 2020.[1]

This helps to explain why one of the themes of 2019 has been a series of reports identifying the high upfront embedded emissions in electric cars and the perils of grids not yet weaned off coal and lignite.

Bloomberg NEF, with Berylls Strategy Advisors, recently claimed that by 2021, ‘capacity will exist to build batteries for more than 10 million cars running on 60 kilowatt-hour packs’, with ‘…most supply … from places like China, Thailand, Germany and Poland that rely on non-renewable sources like coal for electricity.’[2]

Modelling the climate emissions of the manufacture of these batteries led the analysts to claim that the 500kg + battery pack for an SUV emits up to 74 percent more CO2 than producing an efficient conventional car if it’s made in a factory powered by fossil fuels in a place like Germany.

Several other similar reports in 2019 have pinpointed the environmental achilles heel of electric cars – their batteries – some pointing out not just their manufacturing emissions but to other impact categories relating to the mining of battery materials at scale. In some of these reports the claim is that electric cars can be dirtier than diesel cars on an LCA basis, under certain scenarios.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, critics of these reports have been up front in admitting that fulfilling the promise of clean transportation rests on decarbonising the wider energy grid, both in respect of EV manufacturing and EV use-phase. The true potential of electric cars therefore lies in the future.[3]

[1] ‘Life cycle greenhouse gas emission reduction potential of battery electric vehicle’. Zhixin Wu, Michael Wang, Jihu Zheng, Xin Sun, Mingnan Zhao, Xue Wang. Journal of Cleaner Production 190 (2018) p462-470.

[2] www-bloomberg-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/ 2018-10-16/the-dirt-on-clean-electric-cars; Berylls Strategy Advisors, www.berylls.com.

[3] ‘The Underestimated Potential of Battery Electric Vehicles to Reduce Emissions.’ Auke Hoekstra, Joule 3, 1404-1414, June 19, 2019.

Broadly expressed, we acknowledge elements from both sides of this debate and incorporate them in the preparation of individual vehicle assessment. The lowest GHG emission is from hydropower and on this basis an EV in Sweden, as early as 2010, emitted just 6g CO2/km in use; the highest GHG is from lignite and produces an equivalent figure of 353g CO2/km.[1] The authors of this respected academic paper consider that with the current EU grid mix, the emissions of BEVs are between 197 and 206g CO2-equivalent/km, depending on battery chemistry.

At this juncture it is important to emphasise the very promising middle ground occupying the space between ICEV and BEV, the land of the hybrid and plug-in hybrid. In many situations a part-electrified drivetrain can outperform both ICE and BEV owing to the very high embedded emissions in the BEV and its underperformance in cold weather and/or when fuelled from a fossil heavy grid.

In this observation we have in mind one particular paper breaking down drivetrain performance by US regions. The ICE drivetrain had the worst GHG emissions in almost all scenarios, demonstrating the imperative of electrification for climate mitigation in a broad sense; but where cold weather and part-coal grids came into play (typically in parts of the Midwest) the worst performer overall was a BEV, while in all regions the best performing drivetrains were hybrids and plug-in hybrids, partly owing to their ability to scavenge waste heat from an ICE to operate the HVAC system in low temperatures.[2]

As such our default position is technology neutrality respecting acknowledged unknowns. Whereas some reports have claimed that in-use battery degradation could add as much as 29% to the real emissions of a medium size BEV over its life, other studies have noted that the existing durability of batteries in some hybrids suggest that the industry assumption of a lifetime of 150,000km or 8 years (the ‘functional unit’ in LCA language), is excessively cautious, with some early hybrids achieving multiples of this. The truth is that we don’t know because there is not yet enough real-world data to draw on for real-world results.

Where Emissions Analytics will contribute is by modelling an LCA approach premised on the use-phase emissions attained through real-world testing, allowing for a rising scale of other inputs that permit worst-through-best scenarios instead of being captive to a particular model or paradigm.

As things stand there is an emergent consensus view that BEVs can potentially be 30-50% better in GHG emissions, in a whole life LCA perspective, with extensive renewables at manufacturing and in-use, but this is certainly not invariably so.[3] For now, deeming EVs as the cleanest simply by virtue of what they are is misleading.

It’s equally important to note in passing that while climate considerations have become imperative, electrification is something of a devil’s bargain owing to other environmental impact categories that remain far worse than for ICEVs no matter how far projected into a golden future – these include terrestrial acidification; freshwater eutrophication; human toxicity and non-exhaust particulate emissions.[4]

Discrimination by battery origin and market of operation will quickly become an important consideration, and forms the underlying basis of Emissions Analytics’ approach to a ratings model for vehicles.

The other emerging theme is the importance of the duty cycle. The emissions ‘breakeven’ potential of an EV rests on its mileage. It may well be that a small hybrid car remains in LCA terms much more efficient for the occasional or low mileage driver than a full EV.

These and other themes will emerge rapidly as an LCA approach comes to dominate thinking and the regulatory environment. Communicating ratings to car buyers in a comprehensible way will remain Emissions Analytics' mission.

[1] ‘Environmental life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in Poland and the Czech Republic.’ Dorota Burchart-Korol, Simona Jursova, Piotr Folega, Jerzy Korol, Pavlina Pustejovska, Agata Blaut. Journal of Cleaner Production 202 (2018) 476-487, p485.

[2] ‘Effect of regional grid mix, driving patterns and climate on the comparative carbon footprint of gasoline and plug-in electric vehicles in the United States.’ Tugce Yuksel, Mili-Ann M Tamayao, Chris Hendrickson, Inêz M L Azevedo and Jeremy J Michalek, Environ. Res. Lett. 11 (2016) 044007, p8.

[3] This was the finding of BMW in its LCA for the BMW i3 BEV, conducted according to ISO 14040/44 and independently certified in October 2013. The 30% figure assumed the EU-27 grid mix, while the 50% figure assumed 100% renewables. In this study almost 60% of the vehicle’s GHG footprint resulted from manufacturing despite enormous efforts of the company to source renewable energy for production, including all carbon fibre production and the use of re-cycled aluminium.

[4] ‘Environmental life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in Poland and the Czech Republic.’ Dorota Burchart-Korol, Simona Jursova, Piotr Folega, Jerzy Korol, Pavlina Pustejovska, Agata Blaut. Journal of Cleaner Production 202 (2018) 476-487. See Table 9 on p484.

Hybrids are 14 times better than battery electric vehicles at reducing real-world carbon dioxide emissions

Why a multi-pronged approach to electrification is needed

Battery production capacity for motor vehicles is currently scarce, expensive and suffering supply lags and challenges.

Why a multi-pronged approach to electrification is needed

Battery production capacity for motor vehicles is currently scarce, expensive and suffering supply lags and challenges. This may change over time, but for some period securing an economic supply of battery production capacity will be pivotal to the successful commercialisation of electrified vehicles, and to the relative fortunes of individual auto makers. At the same time, electrification is a proven route to tailpipe carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction, or elimination. Therefore, the efficient deployment of available battery capacity between competing applications is critical to maximising fleet CO2 reduction.

So long as this scarcity remains, a major concern is that the push to pure battery electric vehicles (BEVs) will crowd out a more effective programme of mass hybridisation. Put another way, given the urgency of the need to reduce CO2, paradoxically BEVs may not be the best way to achieve it with their supply chain, production capacity, infrastructure and customer acceptance challenges. The assertion that BEVs are required to solve air quality problems is confusing the argument – cities in Europe can be brought into compliance with conventional internal combustion engines, with technology on the market today. Electrification is first and foremost a CO2 reduction technology, but what strategy mix represents the correct path?

This newsletter is inspired by recent insightful articles by Kevin Brown: https://bit.ly/30j50Ed and https://bit.ly/30oC1yM. His insights on the efficiency of carbon reduction can be put together with the Emissions Analytics’ database of real-world testing over almost 100 hybrids vehicles to see in more detail the most efficient options for electrification and CO2 reduction.

As with tailpipe pollutant reduction, CO2 reduction comes down to how to achieve it as cost-efficiently and quickly as possible. Emissions fell during the financial crisis, but at the significant price of sharply reduced economic activity – not desirable. So, how best to deliver road transportation’s part in meeting the Paris climate change targets? The apparent consensus is to transition to pure electric vehicles as rapidly as possible. But is this singular focus better than a combined strategy employing a wide variety of hybrid electric vehicles?

The problem with the pure electric vehicle approach is that the transition will be slow, BEVs need disproportionately large batteries to give acceptable consumer utility, just as battery capacity is currently a scarce resource. As cumulative CO2 emissions are important for climate change – due to the long life of the gas in the atmosphere – a smaller reduction per vehicle now, but across many more hybrid vehicles, would eliminate a far greater volume of CO2 than applying the scarce battery resource to a smaller number of BEVs. This approach also helps mitigate naturally slow fleet turnover, with the average age of cars on the road being over twelve years.

So, what does the real-world performance data of hybrids look like?

The following analysis takes the mild, full and plug-in hybrid vehicles tested by Emissions Analytics in both Europe and the United States. Each hybrid is paired with its nearest equivalent internal-combustion-engine-only vehicle, often the same make and model with a similar engine size. The difference in average CO2 emissions over Emissions Analytics’ standard on-road cycle between the hybrid and its conventional-engined pair is then calculated.

The first table focuses on mild and full hybrids, excluding plug-ins, and shows the average tailpipe CO2 reductions that are achievable with models that are currently on the market, or that have been sold over the last seven years since Emissions Analytics started its test programme.

The average US reduction is larger than in Europe due to the typically higher CO2 emissions starting point of US vehicles, and often the latest hybrid technology is launched in the US market earlier. Of these 95 hybrids, five are diesels.

To put this 30% reduction in context, the EU’s post-2021 CO2 reduction target for passenger cars is 37.5% by 2030. Therefore, widespread non-plug-in hybridisation with currently available technology would achieve over three-quarters of that target. Moreover, with fourth generation hybrids now entering the market, the benefits of hybrids will improve further, as illustrated at https://bit.ly/2KhDlhh. Together with plug-in hybridisation and other design innovations, it is plausible that the target could be met without the need for full electric vehicles.

The results from the first table are then combined with results from plug-in hybrids and a representative BEV, with the difference in CO2 being divided by the battery size of the electrified vehicle. The result measures the efficiency of CO2 reduction in return for the deployment of the scarce battery resource. The results are shown below, with three different illustrative scenarios for plug-ins depending on varying battery utilisation.

* Typical battery size across models currently on the market. The CO2 reduction from BEVs is based on switching from an average internal combustion engine emissions to a zero-emissions BEV.

The table above shows that mild hybrids are clearly the most efficient method of CO2 reduction, followed by full hybrids, given scarce battery production capacity. Plug-in hybrids are the next most effective after that, but only if they are operated entirely on battery, which is hard to enforce in practice. BEVs have the lowest efficiency, primarily due to requiring disproportionately large batteries to accommodate relatively infrequent, extreme usage cases where the driver will otherwise suffer range anxiety.

This analysis ignores the upstream CO2 in fuel extraction, refining and transportation, as well as in the production and distribution of electricity. Some studies suggest the upstream CO2 of the electricity is greater than for gasoline, but the relative efficiency calculations here implicitly assume they are equal.

Showing the distribution of performance by individual model, the chart below relates the efficiency of CO2 reduction by battery size. Mild and full hybrids are the most efficient on average, but there is significant variation within the class – demonstrating that individual vehicle selection remains at least as important as generic powertrain. The same chart also demonstrates the advantage in CO2 reduction that the US currently holds.

In terms of the trajectory to total CO2 reduction, a transition from gasoline internal combustion engine to full gasoline hybrid can reduce emissions by 34%. As it will take time to increase the supply of full hybrids, there are two routes to short-term CO2 reduction that are viable more quickly. First, a switch from gasoline to diesel internal combustion engine in practice reduces CO2 emissions by 11% at the tailpipe. A second step then to a diesel mild hybrid delivers a further 6% reduction. The final swap to full hybrid delivers another 16%, making 34% in total. Alternatively, a direct switch from gasoline to gasoline mild hybrid can deliver 11%, followed by a further 23% in moving to full hybrid. Therefore, there are immediate-term options for significant CO2 reduction, involving both gasoline and diesel powertrains – the former more suitable in the European market, the latter in the US due to the current mix of fuel utilisation.

It is at any regulatory stages beyond the 37.5% fleet reduction that fuller electrification would be required, as there are limits to the total CO2 reduction that hybrids can deliver. However, by 2030 the EU and US would have had more time to develop expanded, cleaner electricity generation capacity, enhanced distribution grid, and addressed the supply chain issues around the scarce materials in batteries. Not neglecting also that consumer education and acceptance are required to remove barriers to adoption. An alternative scenario by 2030 is that the availability and price of renewable electricity may have fallen to a level at which hydrogen fuel cell vehicles become economic viable, which avoid some of the environmental and geopolitical issues created by largescale battery production.

In summary, this data strongly suggests that policy unilaterally favouring one technology solution may be deeply inefficient and perhaps even the wrong eventual solution. A better approach would be to use real-world data to allow competing technologies to flourish as they can evidence genuine CO2 reductions, delivered as soon as possible.

The WLTP enigma

Is there something strange happening with WLTP?

The Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) is the new laboratory certification test for light duty vehicles in Europe. In particular, it is used for the fuel economy labelling of vehicles and the carbon dioxide (CO2) results will be used in labelling and manufacturer fleet average CO2 calculations. Missing the fleet average targets could trigger significant fines for manufacturers.

Is there something strange happening with WLTP?

The Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) is the new laboratory certification test for light duty vehicles in Europe. In particular, it is used for the fuel economy labelling of vehicles and the carbon dioxide (CO2) results will be used in labelling and manufacturer fleet average CO2 calculations. Missing the fleet average targets could trigger significant fines for manufacturers.

WLTP includes a more dynamic test cycle compared to the old New European Driving Cycle (NEDC), although it remains entirely in the laboratory. There is also a new legal framework, which removes some the loopholes and grey areas previously present, which were believed to contribute to the large gaps between certification values and the real world. Therefore, through the combination of the more dynamic cycle and fewer loopholes, the expectation was that WLTP results would see smaller discrepancies with real-world performance.

All cars sold from September 2018 must be WLTP certified, but the fleet average targets are still judged relative to NEDC values. Therefore, a translation mechanism has been created to derive NEDC-equivalent values from the WLTP test. The Joint Research Centre of the EU expressed concern about manipulation of this mechanism in 2018, and tightened the system as a result.

Is WLTP now functioning as intended? How do we judge?

Fortunately, Emissions Analytics has been conducting the consistent, standard EQUA Index test since 2011, bridging both systems. Over 1200 vehicles have been tested so far in this way. Using this data, we are able to compare the old NEDC figures, new NEDC figures and WLTP values to this consistent reference point to understand what has been happening.

There is a vital need to bring clarity, as the WLTP system is complex. Even if data is made freely available, it is hard to understand and analyse. Often, however, the CO2 data is not easily and comprehensively available. The following analysis relies on data quoted by manufacturers in their vehicle registration documents, except where it is demonstrably inaccurate.

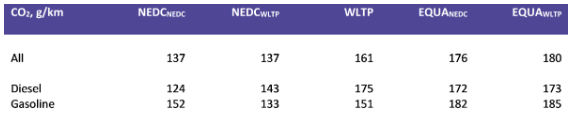

The table below show NEDC values derived under the old system (NEDCNEDC), NEDC values under the new system (NEDCWLTP) and EQUA Index results for vehicles certified under NEDC and WLTP respectively (EQUANEDC and EQUAWLTP). NEDCWLTP results are primarily derived by processing the data from the WLTP test through a software package (CO2MPAS) provided by the EU. The process is complex and, in fact, the NEDCWLTPvalues could be modelled using CO2MPAS, manufacturer declared values or from actual dynamometer tests – therefore, the determination of NEDC-equivalent values under the new system is potentially open to manipulation as its complexity does not assist transparency.

The table summarises the average CO2 emissions for all pre- and post-WLTP vehicles tested up to 3 litres in size. In total, 25 WLTP cars have been tested so far that have a full set of publicly-available data.

To start, it is worth noting that the real-world emissions on the EQUA Index sit well above the current 130 g/km fleet average CO2 target, let alone the 2021 95 g/km 2021 target. But most striking are the differences in trends between diesel and gasoline vehicles, as shown in the table below.

Across all the Euro 6 cars tested prior to the introduction of WLTP, the average CO2 gap was 32%. Cars certified to WLTP over the last one-and-half years show a smaller gap of 13%, as expected. However, below these intuitive headlines are some perplexing trends. For example, the gap between the EQUA Index and the NEDC for diesels has shrunk, while it has expanded for gasoline vehicles – to the point that there is no systematic gap between the EQUA Index and WLTP for diesels, but there is a 24% gap for gasoline.

To verify that this is not an artefact of the vehicles tested, comparing the average CO2 for EQUA results under the NEDC compared to EQUA Index results under the WLTP showed a difference of just 2%. Furthermore, the average engine sizes of the two cohorts were considered, and were broadly similar:

Therefore, it is clear that there has been a significant change in the relative certification values of diesels and gasoline, despite no change in the real-world performance as measured by the EQUA Index.

So, what can we conclude about the health of the WLTP system?

The table below summarises the findings. The comparison of WLTP to NEDCWLTP results is intuitive and in line with EU forecasts. The health of the translation system is primarily being policed by looking at this difference because of the concern that OEMs were simultaneously inflating WLTP values and suppressing NEDC values, to create the biggest gap, so that future WLTP-based fleet average CO2 reductions were based off an inflated start point. The results below suggest this issue is not occurring on a significant scale.

The difference between NEDCWLTP and NEDCNEDC should be positive, as the new type approval framework removes loopholes – but there is a significant negative gap for gasoline vehicles. In other words, CO2 values have fallen despite the test getting tougher. Comparing WLTP to the average NEDC values on under the old regime shows a big rise in CO2 for diesels, but virtually no change for gasoline vehicles.

A potential explanation for these movements is that focus and expertise have been put into optimising gasoline vehicles on the new WLTP cycle, driving the official CO2 down despite this not translating into better real-world performance. The increase in official diesel CO2emissions may be partly explained by the larger average engine size of engines so far tested.

If this turns out to be true, it would give further credence to the argument for including on-road testing in the official CO2 certification process, to limit the ability to optimise to the test. In the meantime, the use of WLTP results for fuel economy labelling will be hardly more useful to consumers that the old, discredited NEDC system it replaced.

European Court annuls Real Driving Emissions limits: the potential consequences

The General Court of the European Union overturned the emissions compliance levels under the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulation in a verdict announced on 13 December. On the surface of it, this may look like a victory for cities wanting to be tougher on emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from passenger cars and vans.

The General Court of the European Union overturned the emissions compliance levels under the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulation in a verdict announced on 13 December. On the surface of it, this may look like a victory for cities wanting to be tougher on emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from passenger cars and vans. In reality, it has the potential to further complicate the Euro 6 regulatory stage and thereby create the unintended consequence of making it even less usable for urban vehicle policy.

While the European Commission did not seek to increase the headline 80 mg/km emissions limit for diesel vehicles, which must still be adhered to in the laboratory test, they granted “Conformity Factors” that in effect did increase the limits for the harder, on-road part of the test. As a result, all diesels vehicles only had to meet 168 mg/km by September 2019, falling to 114 mg/km by January 2021. This was in practice a large increase in the permissible emissions limit.

The Court verdict suggests that vehicles already certified under Real Driving Emissions (that starts with the stage known as “Euro 6d-temp”) will remain compliant, as will vehicles certified for up to 14 further months in the future, depending on whether the Commission appeals and the speed with which replacement legislation is brought forward.

But what is this likely to mean in practice?

Let us assume that there is no appeal and no new legislation, meaning vehicles must meet 80 mg/km on the RDE test. Taking a sample of 30 RDE-certified diesel cars tested by Emissions Analytics on its independent EQUA Index test, we conclude that up to 90% of the vehicles would still be compliant. Although the test does not include cold start in its ratings, overall it remains a good proxy for RDE compliance. Furthermore, the average NOx on a combined cycle of these still-compliant vehicles is just 50 mg/km, well below the certification standard. Of the remaining 10%, they all come from the same OEM, Honda, which would in this scenario need to make changes.

This suggests the impact would be low. However, RDE does not become mandatory for all vehicles sold until September 2019. Therefore, it is likely that this conclusion is flattered due to a self-selecting sample of the best performing cars. If we look at the wider population of pre-RDE Euro 6 diesel cars, we may have a proxy for the challenge to each manufacturer of no Conformity Factors.

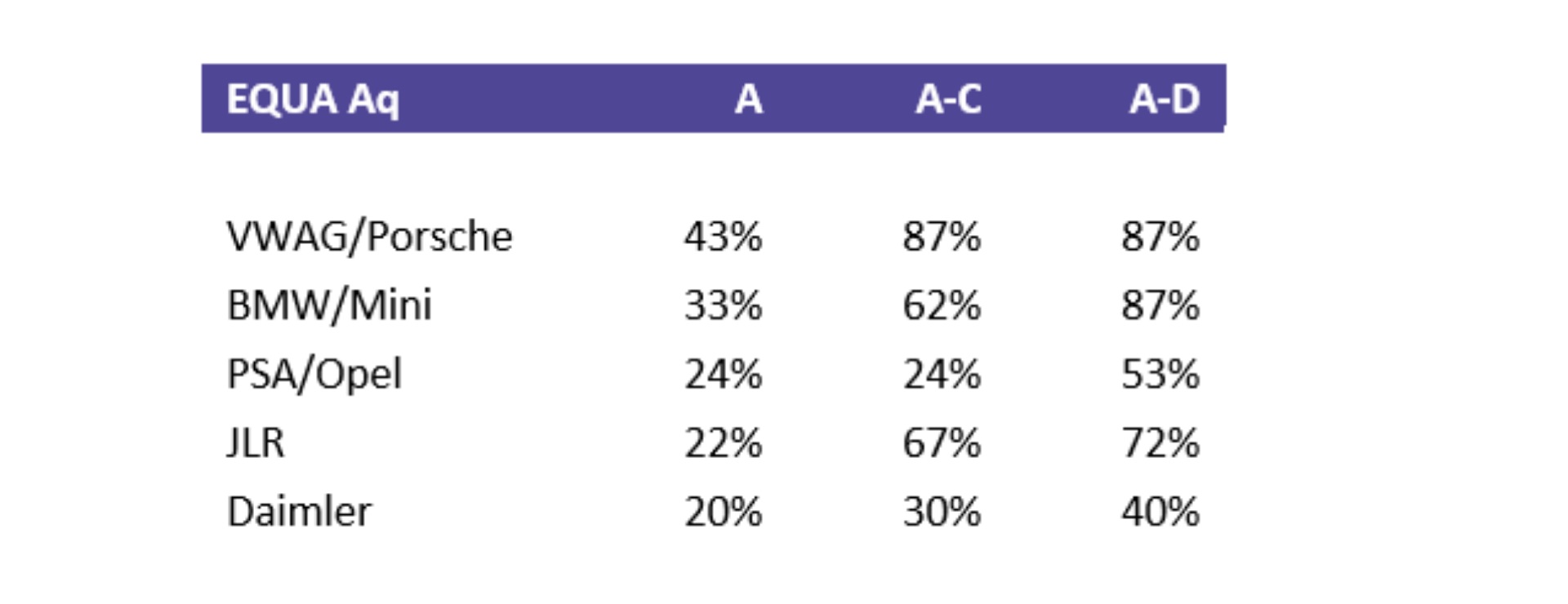

The table below shows the proportion of pre-RDE Euro 6 diesels from a range of manufacturer groups that meet various emissions levels, on our real-world scale. For example, 33% of all BMW/Mini Euro 6 diesel vehicles tested by Emissions Analytics achieve a rating of ‘A’.

The ‘A’ rating is equivalent to 80 mg/km; ‘A’ to ‘C’ is equivalent to 180 mg/km (the Euro 5 level, close to the 2.1 Conformity Factor level); ‘A’ to ‘D’ is equivalent to 250 mg/km (Euro 4).

Approximately, the Conformity Factors allowed ratings of up to ‘C’, but with this annulled, ‘A’ ratings would need to be achieved. The table lists the five manufacturer groups that would be best placed to meet this requirement – assuming their pre-RDE performance is a proxy indicator of how close they are to achieving 80 mg/km across their whole range. VW Group, therefore, is best placed overall; Jaguar Land Rover has made the most rapid advances in the last year.

The final column of the table indicates the proportion that meet ‘A’ to ‘D’. This is relevant to the 270 mg/km maximum limit proposed in an agreement between the German government and cities, to be judged in real-world conditions. The ‘D’ rating is a near equivalent to this level. While the 270 mg/km limit is currently only proposed to apply to Euro 4 and 5 diesels, in time it could be extended to Euro 6 vehicles. If this were to happen, the table shows what proportion of these manufacturers' vehicles may be restricted from the 14 German cities cited. Therefore, VW, BMW and JLR would be the least affected of all. In addition, this is before the benefit of the fixes and retrofits that have been, or may be, actioned, which would further reduce the restrictions. In contrast, there are manufacturers that could face having all their Euro 6 diesels restricted.

Overall, this may give reassurance to some, but there is a wider risk. The annulment of these Conformity Factors further confuses what “Euro 6” means as a label of performance. RDE was meant to be a discontinuity with the past, failed regulation. It had two levels already – two Conformity Factors – but the effect of the Court judgement could lead a change in the gradations or, potentially, more gradations. The Euro 6 label has limited informational content already, but the effect may be to cloud what RDE means, causing further consumer confusion, which would not be to the advantage of the car market.

The Court judgement is witness to the growing power of cities in determining vehicle emissions policy, even if they sometimes demonstrate an unresolved tension between whether air quality improvement or greenhouse gas emissions reduction is the higher priority. What the Court judgement may do is bring into starker relief the difference between the best and worst performing vehicles, which would pave the way for more efficient solutions to the urban air quality challenge.

Real Driving Emissions is a tough regulation, but also a risky one

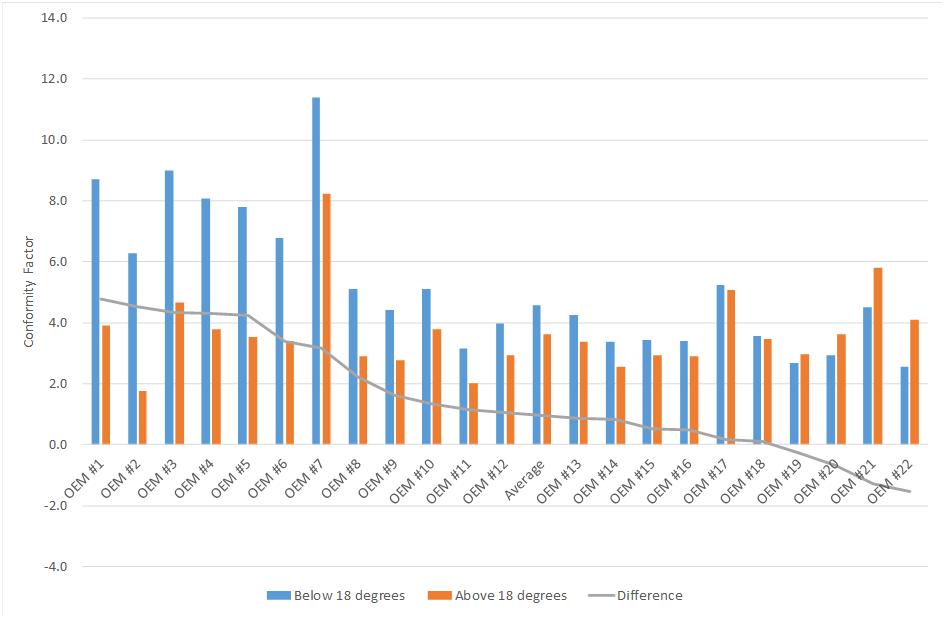

Aggressive driving on average increases pollutant emissions by 35% in rural driving and by around five times on the motorway, according to testing of the latest passenger cars by Emissions Analytics on its EQUA Index programme.

Aggressive driving on average increases pollutant emissions by 35% in rural driving and by around five times on the motorway, according to testing of the latest passenger cars by Emissions Analytics on its EQUA Index programme. Even higher “hotspots” have also been identified, where emissions at high speed can peak at more than ten times typical levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) – the pollutant gas that was at the centre of the #dieselgate scandal.

The need to identify hotspots is becoming vital with the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulations, which is a much tougher regulation of driving in normal conditions. The consequence of this will be that a greater proportion of total emissions may be concentrated in a small number of more unusual or extreme events. Unless those are well understood, the effect of the new regulations may be blunted.

The in-use surveillance requirements set out in the fourth package of RDE are aimed at monitoring vehicle compliance in all normal driving conditions, not just the cycle on which the vehicle was certified. Broadly, a vehicle should pass any RDE test within its useful life, whenever and whoever conducts the test. This is both a significant challenge for manufacturers, and brings with it risk as it is impossible a priori to guarantee compliance on all possible RDE tests.

To help quantify this risk, Emissions Analytics is launching a new evaluation programme that will quantify the risk of excessive emissions for each vehicle tested. Currently, EQUA Index ratings (www.equaindex.com) are published to allow the performance of different vehicles to be compared on a standard, normal cycle. This new programme leaves that rating unchanged, but puts the vehicle through an extended test designed to measure performance in more extreme and unusual driving conditions. The variance between that, the standard EQUA Index and the regulated level will yield a rating for the risk of exceeding the regulated level.

The main factors considered are:

Higher speeds

Higher and lower rates of acceleration

Cold start emissions

Emissions under regeneration of the diesel particulate filter.

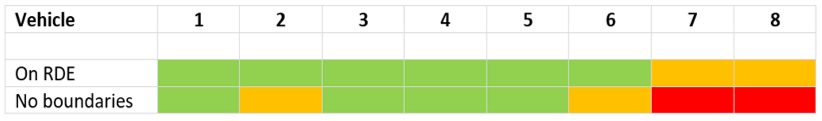

Considering eight diesel cars certified to the new RDE standard (Euro 6d-temp), the effect of driving at speeds up to 160 kph can be shown in the chart below.

In all cases the NOx emissions on the standard cycle – with maximum speeds up to 110 kph – are within the regulated limit of 80 mg/km plus 2.1 times conformity factor, even though certification does not apply this to the motorway section separately. In fact, many of the vehicles are comfortably below this limit. Allowing the maximum speed to rise to 160 kph shows significant proportionate increases on all but one vehicle, with the average percentage increase across all eight vehicles being 552%. All but two of the vehicles remain below the limit despite the increases; however, the worst two vehicles emitted around 650 mg/km.

For reference, under the RDE regulation, the vehicle’s velocity can be driven between 145 and 160 kph for up to 3% of the total motorway driving time. The risk of compliance therefore comes from a vehicle that has a significant emissions uplift at 160 kph and is relatively close to the limit at more moderate speeds.

Under cold start, vehicles 7 and 8 also showed an average increase in emissions of 160% compared to an average of 110% across the other vehicles.

Putting this data together with performance in other parts of the test cycle, it is possible to derive ratings of the risk of excessive emissions on RDE and on RDE-like cycles but with more relaxed boundaries, as shown in the table below.

It is important to note that a red rating does not necessarily imply non-compliance but, rather, it identifies elevated risk of non-compliance using results from the Emissions Analytics’ test, which runs a cycle similar to RDE but that is not strictly compliant.

Considering Euro 6 diesels, whether RDE or prior, the effect of cold start is that NOx emissions are 2.8 times higher on average during the cold start phase compared to the whole warm start cycle. During regeneration of the diesel particulate filter NOx emissions are on average 3.3 times higher than in mixed driving with no regeneration. Therefore, the frequency and geographical location of these events can be critical to the overall real-world vehicle emissions.

These results are important for cities, manufacturers and regulators. For cities, it is vital to know that the latest vehicles do not have emissions hotspots that could undermine their air quality targets. For manufacturers, facing third-party RDE testing to check compliance, it is important to quantify the risk of high emissions being found in unusual driving conditions, where every scenario cannot practically be tested. For regulators, it is important that RDE is seen to function well in order to draw a line under the failed regulation of the past.

Emissions Analytics will continue to test a wide range of the latest vehicles to publish comparable ratings between vehicles, but now with the added quantification of the risk of elevated emissions around the boundaries of normal driving.

Discrepancies between best and worst diesel cars reaches record high

The first diesel vehicle that met the regulated Euro 6 limit for nitrogen oxides (NOx) on our real-world EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) test using a Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) was in May 2013.

The first diesel vehicle that met the regulated Euro 6 limit for nitrogen oxides (NOx) on our real-world EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) test using a Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) was in May 2013. Of the vehicles we tested in that year, the cleanest 10% of diesels emitted 265 mg/km and the dirtiest 10% emitted 1777 mg/km – a ratio of 7 to 1. In 2017, the cleanest 10% achieved an impressive 32 mg/km, but the dirtiest 10% were 1020 mg/km, a ratio of 32 to 1.

On average, progress has certainly been made, with average diesel NOx emissions having fallen from 812 mg/km to 364 mg/km from Euro 5 to Euro 6, or a 55% reduction, driven by the prospect of the new Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulations together with the aftermath of dieselgate. The very worst vehicles have now disappeared from the new car market. It is also true that in around 10 years’ time, the majority of diesels on the road are likely to be of the cleaner variety, through natural turnover of the fleet.

We have now tested six of the latest RDE-compliant diesel vehicles, also known as 'Euro 6d-temp'. Their average NOx emissions were 48 mg/km, 40% below the regulated limit itself, and 71% below the effective limit once the Conformity Factor of 2.1 is taken into account. (As ever, it should be noted that while the EQUA Index test is broadly similar to an RDE test, it is not strictly compliant.) However, it should be noted that there are many cleaner diesels even before RDE, with 30 prior models achieving real-world emissions of 80 mg/km or less.

While this sounds like good news, the elongated transition to RDE, and growing spread from the best to the worst, are creating a growing policy and consumer choice problem in the meantime. A vehicle in the highest-emitting decile today will likely be a significant contributor to urban NO2 pollution. Yet, the cleanest diesels are getting close to the average NOx emissions from new gasoline vehicles, which is 36 mg/km. Without the contemporary data to show this, policy makers would be forgiven for simply banning all diesels from urban locations.

The lowest NOx emission recorded so far this year is the 2017 model year Mercedes CLS, with selective catalytic reduction after-treatment and type-approved for 6d-temp, which recorded 15 mg of NOx per km.

New Real Driving Emissions regulation increases pressure on annual inspection and maintenance testing system

The European Union Roadworthiness Directive came into force on 20 May 2018 and will play a role in enforcing type approval emissions limits, subtly but powerfully changing its role and previous focus on safety, to the benefit of air quality.

The European Union Roadworthiness Directive came into force on 20 May 2018 and will play a role in enforcing type approval emissions limits, subtly but powerfully changing its role and previous focus on safety, to the benefit of air quality.

In the new inspection and maintenance test, known for example as the MOT test in the UK, a ‘major’ defect and automatic fail arises from any visible smoke being emitted by any car equipped with a diesel particulate filter (DPF), meaning in practice the majority of vehicles since late 2009 (Euro 5 onwards).

The definition of ‘visible smoke’ has only tightened up for vehicles registered after 1 January 2014, meaning late Euro 5 and all Euro 6. Permitted smoke for these cars has more than halved from 1.5m-1 to 0.7m-1. This measurement is familiar to any MOT tester and denotes opacity, where 0.0 m-1 is totally clear and 10.00 m-1 is totally black. In practice, less than 0.7m-1 is judged to be invisible and more than 0.7m-1 will be visible.

For vehicles from 1 July 2008 to 31 December 2013, the standard is 1.5m-1, while the smoke standard for older cars remains unchanged, at 2.5m-1 (non-turbo) 3.0m-1 (turbo).

Air quality campaigners have been quick to note the perversity of a tougher test that only applies to newer cars. However, it has long been politically unfeasible to apply new standards to old cars, which would see the wholesale removal of vehicles that met their type approval at the time of their manufacture.

The revised smoke test for vehicles since 2014 is likely to catch out cars where the DPF is absent or defective. Particulate emissions rise by orders of magnitude when the DPF is missing or blocked. In the UK, 1800 cars have been caught without a DPF since 2014, but the true figure is believed to be much higher because it is notoriously difficult for testers to identify DPF removal in the small amount of time taken to perform the MOT.

In an exercise Emissions Analytics conducted in 2017 with BBC 5 live Investigates, a car with its DPF removed still passed its MOT at three (out of three) different garages. Mechanics failed to spot the filter had been taken out on each occasion, and the car was not failed for opacity.

To quantify the difference between having a DPF and not having a DPF, Emissions Analytics technicians tested a 9.0 litre commercial diesel engine before and after the installation of a DPF retrofit. The particle number (PN) and particle mass (PM) afterwards were close to zero, so the reduction was over 99%. Therefore, tampering would increase the emissions by orders of magnitude.

As this problem of DPF removal detection has not been eliminated, it is believed that the tougher smoke test will most likely identify missing filters, although we think a greater degree of tester training and adherence to test processes is also required.

A weakness of the new test is that is does virtually nothing to enforce emissions limits for nitrogen dioxide (NOx). Emissions control equipment is only subject to a visual check for its presence, including the oxygen sensor, NOx sensor and exhaust gas recirculation valve.

Should any of these items be ‘missing, obviously modified or obviously defective’, the car fails the test. However, the new (UK) MOT Manual skimps over this area by suggesting in section 8.2.2.1 (Exhaust emission control equipment for diesel engines), telling testers, “You only need to check components that are visible and identifiable, such as diesel oxidation catalysts, diesel particulate filters, exhaust gas recirculation valves and selective catalytic reduction valves.” We suspect that in numerous cases this requirement will be neglected owing to the continued difficulty of determining the presence of some of these items, or because of commercial pressures to complete tests quickly.

Almost all Euro 5 diesel cars had no NOx after-treatment, just exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), while their Euro 6 successors typically received the addition of either a Lean NOx Trap (LNT) or a Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) system. Therefore, as a rough equivalence, a Euro 6 car with failed after-treatment may emit at a level more akin to an equivalent Euro 5 vehicle.

Emissions Analytics has tested numerous Euro 5 and 6 cars on its on-road EQUA Index (www.equaindex.com) route. For example, a Euro 5 VW Golf 1.6 litre diesel emitted 0.557 g/km of NOx, while its LNT-equipped Euro 6 successor emitted 0.161 g/km, a reduction of 71%.

Then take the larger Mercedes C-Class 2.1 litre diesel. In Euro 5 guise it emitted 1.226 g/km of NOx; and with SCR fitted to the Euro 6 version the same engine emitted 0.396 g/km, a reduction of 68%.

From these results it is clear that to disable these treatments (with an “emulator” or similar) or where they have malfunctioned, NOx could increase by a factor of over 3.

However, the dilemma in setting an in-service NOx standard is that the performance of vehicles when brand new varies from around 20 mg/km to over 1500 mg/km – the issue uncovered as a result of the dieselgate scandal. A vehicle normally producing 20 mg/km that is malfunctioning might produce 800 mg/km, whereas a different model may produce 800 mg/km when in a fully functioning condition. Therefore, a real-world reference number is required to judge the in-service performance. The EQUA Index rating, which is a standardised test on the vehicle when new, could act as this reference value to increase the accuracy of identifying malfunctioning vehicles.

One unmistakable outcome is that what was once mainly a test for roadworthiness has now become a more complex enforcement of type approval emissions, at the very moment when those limits are tightening up within WLTP/RDE.

The inspection and maintenance system has in this sense risen in importance as a tool for policing emissions, because non-compliant vehicles will display vastly increased emissions, by orders of magnitude. However, the failure to test properly for NOx misses one of the major problems that Europe faces, in the wake of its dieselisation, while the ultrafine particles produced by downsized, direct injection petrol engines are also missed. It feels as though the new test is distinctly lacking in these crucial areas, leaving much more work to be done.

Rethinking Scrappage For Addressing Vehicle Emissions

Scrappage schemes are controversial. In a 2011 academic paper* reviewing 26 studies assessing the outcomes of 18 scrappage schemes implemented around the world in 2008-11, the authors concluded that the emission effects of the schemes were ‘modest and occur within the short term.’ They also concluded that the cost-effectiveness of such schemes ‘is often quite poor.’

Scrappage schemes are controversial. In a 2011 academic paper* reviewing 26 studies assessing the outcomes of 18 scrappage schemes implemented around the world in 2008-11, the authors concluded that the emission effects of the schemes were ‘modest and occur within the short term.’ They also concluded that the cost-effectiveness of such schemes ‘is often quite poor.’

The reality of the 2008-9 scrappage schemes, however, was that governments in Europe, the US and Japan were tackling a liquidity gap by stimulating consumption and bolstering an ailing car industry. The mooted environmental benefits of accelerated fleet renewal were talked up by politicians but were not the main objective. This helps to explain why the efficiency of the schemes in mitigating Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions - CO2 dominating discussion at the time - was found to be poor value for the taxpayer and of marginal consequence to overall path reductions towards a low carbon economy.

Since 2008-9, the policy climate has changed significantly, with air quality emerging as a major concern. Several national governments have been sued by environmental groups for illegal levels of NOx in cities, and what was once a transport policy issue has become a matter of public health. With diesel bans looming in city centres, plus the advent of clean air zones, it’s no stunt to reimagine scrappage according to an emission-reduction imperative.

Data availability upon which to base an intelligent scrappage scheme has also improved. Since 2011 Emissions Analytics has compiled the world’s largest database (the EQUA Index) of standardised real-world emissions tests, of over 2000 cars. The EQUA Index test measures not just CO2 emissions but nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and carbon monoxide (CO), as well as fuel efficiency.

Reimagining scrappage in light of air quality first requires accepting that the now discredited New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) test regime has produced counterintuitive outcomes, to the point where some of the newest cars are by no means the cleanest. This means that a poorly designed scrappage scheme could produce a worse outcome, measured in air quality, than doing nothing at all.

The EQUA Index results show that:

Dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are 6-7 times worse than cleanest Euro 5

Dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are up to 3 times worse than cleanest Euro 3/4

Some 20-year-old cars are cleaner than some brand new cars

How one weights GHG emissions against NOx emissions is a matter of policy debate and public acceptance, but a plausible objective would be Pareto optimality, or the idea that addressing air quality should not be at the expense of GHG such as CO2. While research points towards life cycle or ‘well to wheel’ analysis of CO2 emissions, this is difficult to measure and for the sake of a near-term scrappage scheme probably lies in the future.

Beyond the well-observed conflict between efficiency, where diesel scores well compared to gasoline, and the point-of-use emissions, where gasoline is consistently cleaner with respect to certain emissions such as nitrogen dioxide, the point to make is that it is possible to target and scrap dirty cars without increasing CO2.

The EQUA Index test recently revealed that 11 Euro 6 diesel cars from four manufacturers merited an A+ rating, equivalent to 0.06 g/km NOx in the EQUA Index test, which compares with a limit 180% higher (0.168 g/km NOx) for the new RDE requirement that will prevail until January 2021. Such cars can be said to be genuinely clean by today’s standards, but were greatly outnumbered by highly polluting diesel models, 38 of which scored F, G or H, meaning that they exceeded the Euro 6 limit in respect of NOx by 6-15 times. By comparison, 105 gasoline and hybrid Euro 6 cars achieved the A+ rating, and only one gasoline model fell into the D category, the rest being C or higher.

In the graph above, the arrow labelled ‘Bad Trade’ travels from a Euro 4, 1.9-litre diesel Skoda Octavia, model year 2009, that scored E in the EQUA Index test, towards a Euro 6, 1.6 litre diesel Nissan Qashqai, model year 2016, that scored H in the EQUA Index test. The Skoda is cleaner than the Nissan in real-world testing, yet a scrappage scheme designed around vehicle age alone could result in the cleaner Skoda being scrapped for purchase of an equivalent, dirtier Nissan Qashqai. This would result in tailpipe emissions higher by a factor of more than five and therefore worse air quality. It would be a waste of tax payer money.

Conversely the ‘Good Trade’ arrow highlights that dirty older (and conceivably newer) vehicles could be scrapped for genuinely cleaner new vehicles. Currently, 87% of Euro 6 diesel cars are over the Euro 6 limit, as are all Euro 5 cars. If all these cars were replaced by Euro 6 cars actually performing to the Euro 6 diesel standard in real-world conditions, the net tailpipe emissions improvement measured in NOx would be around 88% from the Euro 5/6 fleet. If real-world performance were only brought down to the Euro 5 diesel standard, the reduction in emissions would be 74%. Even if performance were reduced to just Euro 3 levels, there would still be a 38% reduction.

Put another way, as most Euro 5 and 6 diesels emit over the limit, a large number of vehicles need to be “fixed” to address the air quality problem. This inherently makes any scrappage scheme highly costly. Therefore, a more stratified approach may be optimal, as shown in the chart above. Emerging passenger car retrofit technology may deliver a 25% or more reduction in NOx; those vehicles with moderately high emissions could be tackled in that way. A scrappage scheme could then be targeted on the dirtiest diesels (perhaps worse than the Euro 3 level in real-world).

A further potential ‘Bad Trade’ may be switching from a diesel car to a non-hybridised gasoline car. The same vehicles viewed through the lens of CO2 emissions show that on average, gasoline vehicles are, like-for-like, a ratings class worse than diesels for absolute CO2 emissions. They also exhibit a greater disparity between NEDC measurements and actual emissions. For example, the 2017 Audi Q2 diesel, achieves A+ for air quality and C2 for CO2. The same power output gasoline equivalent model from the same year also achieves A+ for air quality, but a lower D4 for CO2. C means 150-175g/km CO2; D means 175-200 g/km, but the numbers 2 and 4 respectively show that the gasoline engine model is at greater variance from the officially claimed figures. This example highlights an element of the trade-off involved if tackling air quality results in a more gasoline-dominant fleet.

In summary, the right scrappage and retrofit schemes could incentivise consumers towards vehicles that are genuinely clean and genuinely efficient, taking into account not just NOx emissions, but also CO2 and particulates. This would contrast with the UK’s 2009 scheme that merely required customers to scrap their old car for any new vehicle. A stratified and discriminating scheme would require a more focussed replacement, resulting in better results both for air quality and climate change.

* Bert Van Wee, Gerard De Jong & Hans Nijland (2011) ‘Accelerating Car Scrappage: A Review of Research into the Environmental Impacts’, Transport Reviews, 31:5, 549-569, DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2011.564331

Cutting pollution and improving public health

Pollution is a major contributor to chronic human sickness, not just environmental damage, according to the 2017 annual report of England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, released on 2 March 2018: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know. The report made 22 policy recommendations, many of which related to monitoring and ameliorating pollutant emissions.

Pollution is a major contributor to chronic human sickness, not just environmental damage, according to the 2017 annual report of England’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, released on 2 March 2018: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officer-annual-report-2017-health-impacts-of-all-pollution-what-do-we-know. The report made 22 policy recommendations, many of which related to monitoring and ameliorating pollutant emissions.

Emissions Analytics is pleased to have had its EQUA Index real-world emissions rating system (www.equaindex.com) cited in the report. With the failure of the previous EU vehicles emissions regulatory regime, having led to around 40 million high-NOx-emitting diesels on European roads, the need to base policy on real-world emissions has grown, as illustrated in the chart below. Each point represents a vehicle we have tested, and the horizontal line shows the regulated limits.

It is clear that at each Euro stage the cleanest vehicles have been getting cleaner, while the dirtiest vehicles have not. Therefore, any system of discriminating between vehicles based only on Euro stage will be highly inefficient as it will involve permitting some vehicles with high real-world emissions. The particularly problematic Euro stages are 5 and 6, within which there are significant spreads from the best to the worst. For example, the dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are six to seven times higher emitting than the cleanest Euro 5. More striking still, the dirtiest Euro 6 diesels are around three times worse than the cleanest Euro 3/4 vehicles, last of which were type-approved in 2009.

In summary, using the EQUA Indices would allow governments and cities to target only those vehicles which are high emitting in practice, minimising the private and public cost. Any system based only on official Euro standards would be costlier and less efficient. Estimates of the benefit suggest that 54% of Euro 6 diesels would have to be restricted from urban areas to achieve an 87% reduction in nitrogen oxide emissions.

Many of the Chief Medical Officer’s recommendations revolve around the need for evidence-based action. This has been dramatically lacking in emissions policy, due to the difficult choices it would present.

One recommendation specifically calls on local government and public health professionals to implement concrete solutions. The Mayor of London’s publishing of the EQUA Aq ratings for NOx on its official website (www.london.gov.uk/cleaner-vehicle-checker/) is an example of proven action that could be applied in any city across Europe. Another recommendation talks about providing toolkits to assist local authorities. With the challenges of Clean Air Zones, the priority is to link up the existing empirical evidence with policy action on the ground.